Hero image credit: Rontti Varjola / We Animals

As global fisheries collapsed in the late 20th century, corporations pitched fish farming as a silver-bullet fix—a “Blue Revolution” that would feed the world while restoring wild populations. Over the past four decades, this narrative has powerfully shaped how we think about seafood, with consumers, policymakers, environmentalists, and food service leaders being led to embrace farmed fish as an ecologically sound solution.

As global fisheries collapsed in the late 20th century, corporations pitched fish farming as a silver-bullet fix—a “Blue Revolution” that would feed the world while restoring wild populations. Over the past four decades, this narrative has powerfully shaped how we think about seafood, with consumers, policymakers, environmentalists, and food service leaders being led to embrace farmed fish as an ecologically sound solution.

This promise of sustainability obscures the fact that industrial fish farming is the next wave of factory farming. Behind its carefully crafted image lie crowded cages, the exploitation of wild fish for feed, rampant disease, and misleading marketing and labels.

Here we present five enduring myths that built this illusion, paired with evidence exposing them as greenwashing.

A note: While the term “aquaculture” can refer to many different species, finfish and shrimp farming dominate the global market and account for the vast majority of the ecological and public health risks described here. Plant-based aquaculture systems such as seaweed and kelp farming, on the other hand, offer unique environmental benefits, which is why they are not part of the myths explored here.

Rather than reducing the burden on wild fish, fish farming depends on industrial fishing. Feeding carnivorous species like salmon, trout, and sea bass requires small fish like anchovies and sardines ground into fish meal and oil. Roughly one-quarter of the world’s marine catch is reduced into fishmeal and fish oil each year, most of which is consumed by farmed fish.1

Scientific analyses reveal how inefficient this system truly is. A Science Advances study found that the industry’s primary feed efficiency metric underestimates wild fish inputs by roughly 300 percent, revealing that salmon, in particular, consume up to five times more wild fish than they yield.2

This inefficiency in converting feed to protein holds true for non-carnivorous species, too. According to the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, across nine major farmed fish species, only 19 percent of protein and 10 percent of feed calories are retained for human diets.3 Across the sector, just like farming land animals, fish farming produces a net loss, draining wild ecosystems and undermining global nutrition.

Aquaculture’s high demand for resources weighs most heavily on vulnerable ecosystems and populations. Much of the fish used as feed comes from fisheries in West Africa and South America that are already in steep decline. As pressure intensifies on these depleted populations, the consequences cascade onto coastal communities that have long depended on them for daily nutrition. So-called “sustainable” seafood produced for wealthy nations, therefore, comes at the expense of the Global South.4

Instead of replacing wild-caught fishing, aquaculture has stacked on top of it. Per-capita intake of sea animals has more than doubled since 1960, when intensive aquaculture was first being developed, rising nearly twice as fast as the world’s population.5 In other words, aquaculture isn’t feeding more people; it’s enabling existing consumers—especially in wealthy countries like the U.S.—to eat much more fish, including wild-caught, at increasingly unsustainable levels.

To generate this demand and ensure its own growth, the industry has manipulated both consumers and policymakers. In the 1980s, for instance, Norwegian salmon producers launched “Project Japan,” a campaign to make raw Atlantic salmon seem healthy, safe, and trendy. At the time, Japanese consumers associated salmon with disease and parasite risk. The industry paid chefs, bought ad placements, and rebranded salmon as part of Japanese culture, seizing the opportunity to capture a global market just as sushi was becoming popular worldwide.6

In Chile, foreign salmon corporations pushed the government to grant them exclusive coastal concessions—effectively private property rights—in public waters, thereby reducing regulatory oversight.7 During a catastrophic red tide in 2016, the government—under industry pressure—approved dumping nearly 5,000 tons of salmon carcasses offshore, worsening the disaster and leaving Indigenous fishing communities to clean up beaches littered with dead wild fish.8

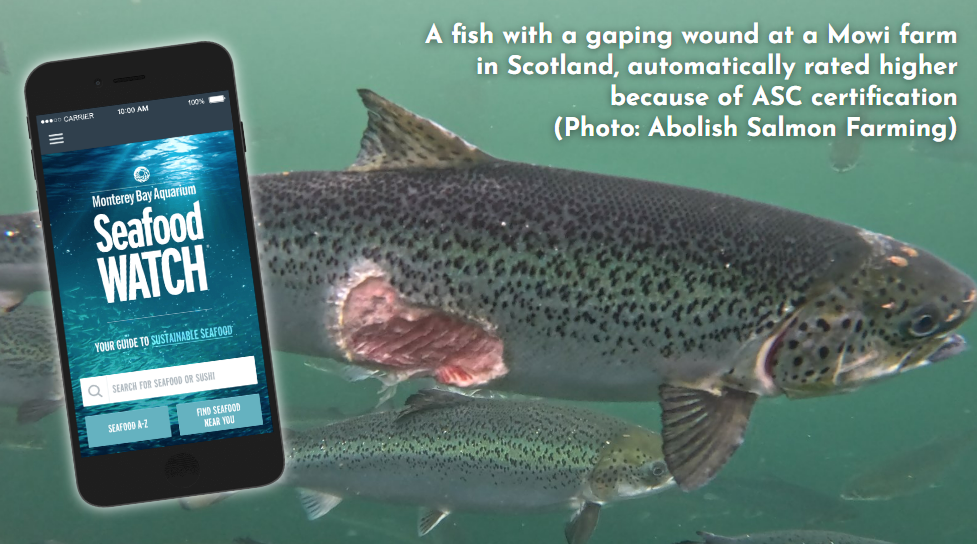

Behind images of “clean ocean protein,” industrial fish farms confine hundreds of thousands of animals in pens so crowded that waste, parasites, and pathogens spread unchecked—mirroring land-based factory farms. In salmon farms, sea lice eat away the fish’s scales and skin, leaving open lesions.9 Shrimp ponds are ravaged by viral diseases such as white spot syndrome, which destroys shrimps’ internal organs within days.10

Consequences stretch beyond the farm to the consumer. Each year, about 260,000 people in the U.S. are sickened by fish and shellfish, many from aquaculture products.11 A 2023 study detected Vibrio bacteria—which can cause diarrhea, vomiting, sepsis, and even death—in 60 percent of California retail shrimp samples.12

To keep these disease-prone systems afloat, fish farms, like land animal farms, depend on antibiotics critical to human medicine, and the sector is poised to have the highest use intensity of these drugs out of any farmed animal sector by 2030.13 These drugs, which seep into surrounding waters and even persist as residues in sea animal products, risk accelerating antimicrobial resistance—the evolution of bacteria that no longer respond to treatment—worsening a crisis the World Health Organization ranks among today’s top global health threats.14

Making matters worse, despite the fact that many drugs are banned in fish and shellfish produced in and imported to the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration only tests 0.1% of shipments, allowing contaminated products to reach store shelves.15 Antibiotics are entirely banned in shrimp, but a recent Louisiana study found residues of the illegal drug nitrofurantoin (an antibiotic important for the treatment of human disease) in 70 percent of farmed shrimp retail samples.16

The seafood industry has successfully positioned farmed fish as a low-carbon protein, convincing many eco-conscious organizations and foodservice establishments to feature it in their climate commitments. But the numbers tell a different story: producing one kilogram of farmed fish emits, on average, about 13.6 kg CO₂-eq—comparable to pork, greater than poultry, and more than thirteen times the emissions of legumes.17 Most of this comes from feed production, which depends on wild fish and soy linked to deforestation and land-use change.

Shrimp farming is even worse, generating roughly twice the emissions of finfish aquaculture.17 Further, since the 1980s, shrimp farming has driven around 38 percent of global mangrove loss (more than half of which has occurred in Southeast Asia). Because mangroves store up to five times more carbon per hectare than tropical forests, their conversion into ponds turns essential carbon sinks into major emissions sources.18

High mortality inflates aquaculture’s carbon cost even more. In 2023, Norway’s salmon industry reported 63 million premature deaths—17 percent of all fish—squandering the feed, fuel, and antibiotics already invested.19

Switching back to wild fish does not offer a solution. Even the lowest-emitting wild fisheries still carry far higher carbon and ecological costs than plant proteins, and industrial fishing brings its own harms: bycatch, habitat destruction, collapsing wild fish populations, and the continued extraction of ocean life already pushed to the brink.

Certifications like the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) and Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP)—along with consumer guides such as Seafood Watch—are promoted as proof that farmed fish meets rigorous sustainability standards. These assurances have convinced many consumers, universities, and companies that they can buy “responsibly farmed” fish with confidence. Many of the people who work within or support these systems genuinely want to safeguard oceans, but these programs aren’t built to deliver that.

Certifications like ASC and BAP are run on industry funding from certification and audit fees, tying their financial success to certifying—and recertifying—farms.20 21 This structure inherently discourages strict oversight, with many farms within a company’s “group” exempt from annual third-party audits, and helps explain weak, inconsistently enforced standards.

Both ASC and BAP allow routine antibiotic use, including drugs critical for human medicine, and do not impose strict limits against disease and mortality.22 23 ASC recently loosened its sea lice threshold in British Columbia by more than 1,500%, permitting parasite levels scientists warn are lethal to wild salmon, while BAP has no threshold at all.24 When farms fail audits, they often remain certified. A SeaChoice study, for example, revealed that nearly 80% of audited farms did not fully meet the ASC standard yet still retained the certification.25

In addition to certifications, Seafood Watch is the most trusted consumer seafood guide and plays a key role in purchasing decisions made by many shoppers. But Seafood Watch rates entire species in broad regions, which means an area can get a green light without anyone ever verifying whether a specific farm is using illegal antibiotics or is plagued by lice and disease.26 Further, ASC-certified farms are automatically scored more favorably simply because they carry the ASC label, despite the trail of evidence of ASC’s failings.

Together, these programs have convinced us that we are choosing the responsible option, when in reality, they’re steering us toward supporting factory farming at sea. They have become powerful instruments of greenwashing to help the industry profit at the consumer’s expense.

For decades, fish farming has been hailed as a way to eat more sea animals without harming the oceans. Many conservationists, scientists, and philanthropic leaders embraced this vision in good faith, motivated by a genuine desire to protect marine ecosystems. But the industry spent just as long crafting a narrative that downplayed its harms, misleading even the most well-intentioned voices.

The evidence shows that we simply cannot produce fish at today’s scale—whether by farming or by fishing—without accelerating ecological decline. The most effective solution is also the most straightforward: eating less fish and shellfish in the first place. Many restaurants, workplaces, and schools are already demonstrating that reducing animal proteins and offering more plant-based foods is practical, affordable, and widely supported.27

True ocean protection will come not from better labels or “responsible” sourcing, but from lowering the overall volume of fish produced and consumed, especially in the U.S. Cutting back is essential to easing pressure on wild fish, restoring coastal ecosystems, and addressing the climate crisis.